‘We are still burning’ – survivors of Beskdira and Ona massacre

Fifty years ago, Beskdira and Ona witnessed two of the worst massacres in Eritrea’s colonial history when unarmed civilians were brutally massacred by Ethiopian colonial troops. While Beskdira is a small village about 20 kilometres northeast of the city of Keren, Ona is located just at the outskirts of the city. Both villages were burned to ashes, one after another, in a matter of two days by the colonial army in retaliation for the killing of Ethiopian Major General Teshome Ergetu. In this reflexive blog, I provide an insight into what happened in these villages fifty years ago and highlight survivors’ stories.

In Beskidira, on 30 November 1970, the colonial army savagely killed over 120 defenceless unarmed civilians. In fact, the residents of Beskdira had gathered together to welcome the Ethiopian soldiers hoping that a welcome gesture would deter them from burning the village. Following an initial deceitful indication of a peaceful meeting, however, the heavily armed soldiers took the terrified villagers hostage for a couple of hours while waiting for the final orders as to what to do with them. After they received information from their commanders, the armed soldiers attempted to separate the inhabitants of the village into groups of Christians and Muslims. The villagers, however, courageously refused to be separated and explained their preparedness to die together rather than being divided on religious grounds. When asked whether they were Christians or Muslims, Meriem (not her real name) recalled the villagers’ response as follows:

We are both Christians and Muslims. But, above all, we are sisters and brothers… We are the same people: our blood and flesh are the same. We attest our innocence and beg you not to annihilate us, but if the choices you offer are between death and division, we are prepared to die together.

Unhappy with the uncompromising response, the troops ordered all the villagers (Christians and Muslims, men and women, adults and children) to gather inside a mosque and then indiscriminately massacred them with their semi-automatic guns; over 120 people were viciously killed, many were seriously wounded, and infants were left clinging to the nipples of their dead mothers. The massacre was one of the most brutal in the history of the Ethiopian colonisation of Eritrea. For readers of the Tigrigna language, the list of the murdered civilians and details about the atrocity can be found here.

A day after the carnage in Beskdira, Ona became the next target. The village was subjected to overnight artillery shelling and then, during the day, on 1 December 1970, armed troops came to the village on their military cars and aimlessly bombed the entire village. In minutes, Ona was turned to ashes and its inhabitants to charred bodies; over 800 unarmed civilians were either burned inside their houses or brutally shot to death. The people of the surrounding villages and the city of Keren watched in horror at what was unfolding in front of their eyes. Survivors’ stories of the human depravity are beyond imagination. Jabaraya Media has a recently salvaged comprehensive account of survivors’ stories and histories on its Facebook Page.

Talking on social media, the survivors appealed to the young generation to honour the victims. Among other things, they suggest three things that we can do to honour the victims’ ideals. First, we must recognise their untold suffering and salvage what is left of their stories of misery. Those survivors who were found nipping at their dead mothers in the wake of the tragic incident and who grew up hearing the tragic stories should not be left feeling abandoned and that the promises of their generation are being ignored. This is not to underestimate the work that has been done so far by Eritrean professional and researchers. In fact, we must acknowledge and celebrate the enormous work of preservation that has already been done and build on it. In this digital era, creating a documentary and conducting a salvage ethnography are some of the viable options of preserving the untold stories of the past generations.

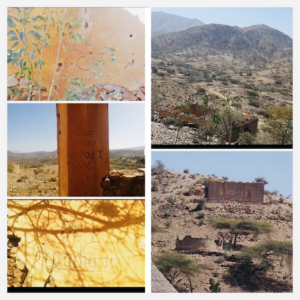

Second, we must address the survivors’ fear that the historical sites, which still bear traces of the enormous human suffering to which they bore witness, will soon become ruins. As you can see in the image below, for example, every brick of the mosque where the massacre was perpetrated in Beskdira represents a forgotten history of human anguish. The names and stories of the victims are written on the walls by those who bore witness to the tragedy, along with blotches of the victims’ blood where it splashed and the holes created by the enemy’s bullets. Discoloured by the blood of those who suffered the barbaric cruelty, the dirty floors of the mosque in Beskdira and burned stones of Ona represent a personalised, ritualised and memorialised history of the Blin people of Eritrea. Fifty years later, however, the survivors are watching as the historical site and its monuments collapse before their eyes. It is now our turn to preserve these historical sites before they have reached a point where we can no longer maintain the monuments intact.

Last, but not least, we can embrace our ancestors’ collective aspirations of respecting one another and living together in harmony. If our ancestors stood together with one another in the worst of times, healing should not divide us. Social solidarity, community cohesion and resilience are some of the preconditions for us as a people and nation to heal ourselves from the collective trauma of the dark past. The carnage of Beskdira and Ona can only afford us a snapshot of the colonial devastation, so we must broaden our efforts to reconstitute what was left destitute by successive colonial powers.

In the end, we must never forget the charred bodies, the burnt villages and the visceral pain of the survivors. The apocalyptic imagery of the destruction of the village and the human suffering of the inhabitants still remain fresh in the minds of the survivors. As Haile (not his real name) articulated, the survivors assert: ‘We have not forgotten the pain even for one second… We are still burning and will die burning in honour of those who died before us’. Our history as a people and a nation is built on the ashes of those burnt villages, the blood of the human victims and engrained trauma of the survivors. Barbaric acts of violence such as the Beskdira and Ona massacres were orchestrated to instil fear of not only the cruel colonial army but also life itself. The colonised subjects were relegated to a form of ‘life for which what is at stake in its way of living is living itself’ (Agamben, 2000, p. 3). Yet, they have never succumbed to fear and violence. Instead, they yearn for the freedom to breathe free. They put their lives on the line for freedom from oppression and the incessant violence they were subjected to. In doing so, they hoped for a better future for their children, the generations to come and their country. As a society, we must rediscover these deferred hopes and dreams and pursue them.